There’s been a lot made lately of Kamala Harris’ racial identity. This whole horrible chapter in our American history is driven by racism. Actually, throughout history around the world, it’s almost always been about racism. Black Like Me was one of the most impactful books I read back in high school. It’s the story of a white journalist, John Howard Griffin, who used dermatologist treatments and other tactics to change his appearance from Caucasian to Black back in the 1950s segregated South. He wanted to see what it was like to be Black. I did something like that as well, unintentionally, and here’s what I learned.

Project: Pioneer is the live weekly reality journal of a couple and their small dog as they leave their ‘normal’ life in a luxury apartment for a new semi-off grid life in a small recreational vehicle. We cover prepping, politics, spirituality, afterlife, RV life, and personal finance. Half of all subscription/donation money goes to The National Alliance to End Homelessness, the other half pays for expenses. You can listen to the audio podcast version of this journal at Substack, Apple, Spotify, PocketCasts and others.

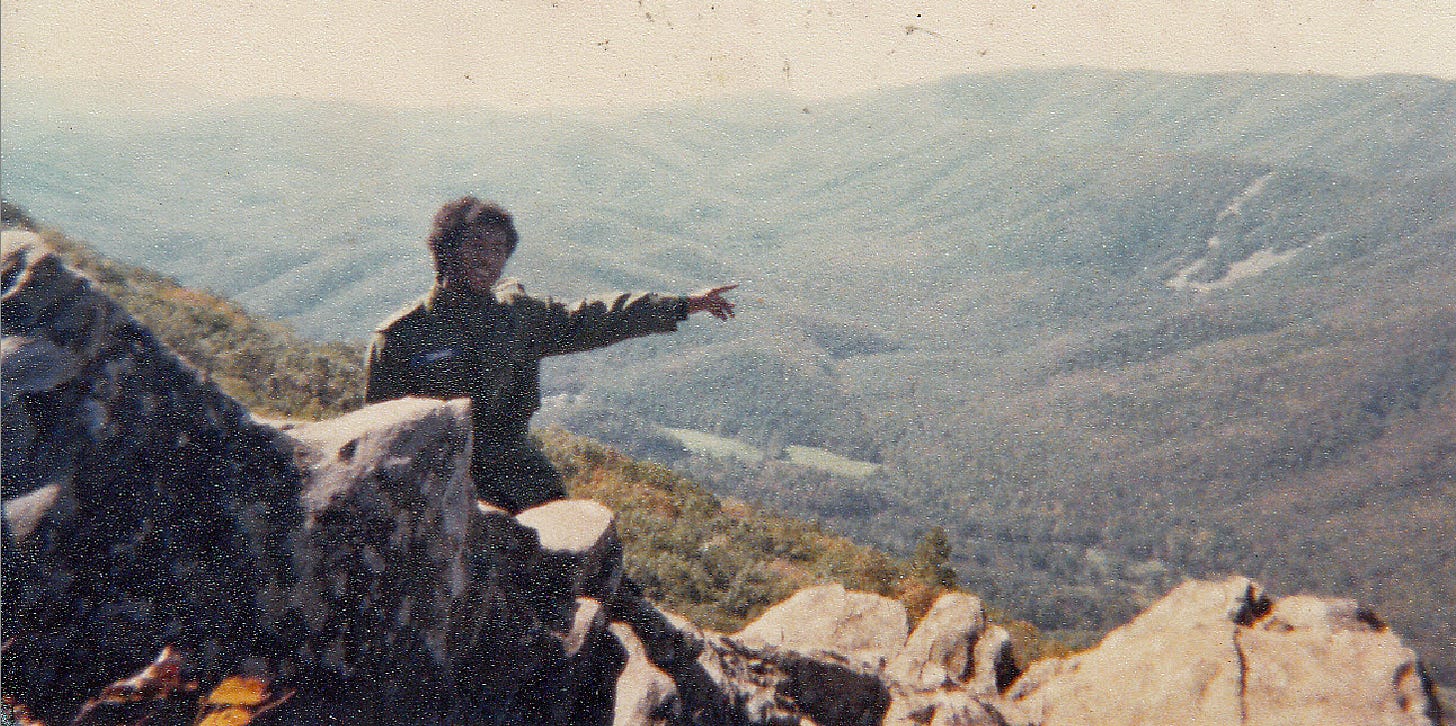

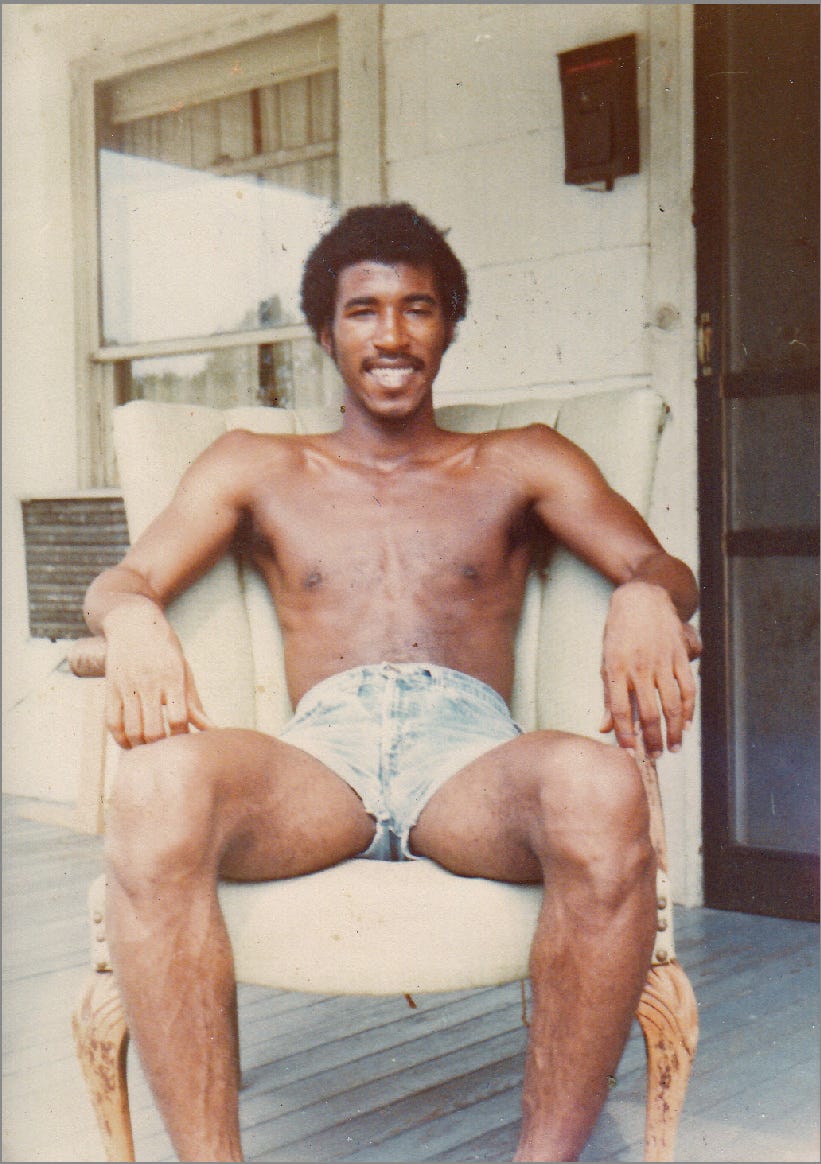

Back in the early 1980s, I traveled the South with a Black dude I’ll call Damon (which I also did in Farawayer). He was one of a kind—a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. We were both fresh out of ungraceful exits from our military service, lost and broke young men trying to find our way through life. Damon was part Marvin Gaye, part Malcolm X, part Muhammad Ali—a poet, a politician, a philosopher, an artist, a lover, a radical, a fighter. Highly intelligent, yet not highly educated. He could never understand why he was treated differently than White folks.

When we hitchhiked, traveled, and lived in the South, whenever I was with him, I was as good as Black to everyone else. My long hair didn’t favor me with that same ignorant redneck demographic, on top of being in the company of someone who looked like Damon.

A pickup came toward us and slowed down as the driver and passenger windows rolled down. A huge confederate flag adorned the hood. Two fat, short-bearded rednecks leered out the windows at us, wearing T-shirts with the sleeves cut off. “Nigger, nigger, nigger!” they shouted. “A nigger and a nigger-lover!”—Farawayer

Those days were an unintentional perfect case study in racism. We were the same age, same height/weight, same background as high school grads and veterans, both pretty well spoken. However, time after time we applied for the exact same jobs—low level stuff like maintenance man, store clerk, warehouseman, and I’d get the job and he wouldn’t—except when we applied together. In those cases, neither of us did. To them, I was as Black as he was. I was proud of it, but in my case it wasn’t a permanent condition. I was lucky.

I snapped in my exhaustion and state of despair, and dropped my pack, running after the truck. “Let’s go then, you fat fucks. Man up!” I shouted. The truck slid to a stop and the lone working white backup light blinked on, like an ogre suddenly waking. Damon ran up beside me and threw his bag to the curb.—Farawayer

Time and again we’d enter stores to grab some groceries. I’d hide my hair up under my Stetson, but Damon couldn’t hide his Blackness. We’d go our separate ways once inside, to get the things we needed, and I’d always watch as the inevitable would happen—the store clerk or security person would begin to follow him around the store. Sometimes, they’d make an accusation. A cop car couldn’t pass us walking on the roads without stopping to “investigate.” We had no car, most of the time, at least not one that worked. It broke his good heart, and he’d be down the rest of the day over it.

“Damn, Levi. Get ready for Ali mode. Better hope these white boys fight like Jerry Quarry. You still undefeated?” Damon asked.

“I’ll let you know in a few minutes, brother.” We had both been on the base boxing team a few years back. “You know the drill,” I said. “Same as always. They’re out of shape. Make them move and wear them down.”—Farawayer

I was born in Newark, NJ and started school there. I learned at that young age, with lots of Black kids in my kindergarten class, that color doesn’t matter. Good and bad come in every color, shape, and religion. We moved to a suburban White neighborhood, and I missed the diversity. Everyone was the same color.

“Rope-a-dope again,” Damon said as the two fat men flung the truck doors open and waddled toward us. Damon took his stance and called out to them as they approached with their fists up. “Just like Muhammad Ali, I'm gonna sting you like a bee, son.”—Farawayer

In my youth, I often heard the adults talking about “the Blacks,” and how they just wanted handouts, welfare, didn’t want to work. How casually they threw around the n-word! Sometimes, it would be in the presence of Hispanics, who would then get crapped on too, as soon as they were out of earshot.

In my travels with Damon later in life, I saw the truth. You have to work twice, three times as hard to get work. Then you have to work even harder so you don’t get fired. Folks who are born on second base as a white person, especially a male (perhaps third base in that case) don’t realize it, especially since they have their own (comparatively mild) struggles. They’ve never spent time as a Black person like John Howard Griffin and I did. They’ve never lived around Black or Brown people. Or any other Other, hence the fear, hence the hatred of anyone different from them. There’s a section in my book about when I had nowhere to go, nowhere to live, and a gay friend of a friend took me in, so I got to experience that side of hate as well. Same drill. I called him Barry in the book, and he died a horrific death from AIDS while still a young man. He didn’t deserve it.

We fear what is different, and the unknown. Our mind isn’t familiar enough to have protections. We yearn to be surrounded with familiarity, for comfort, hence the utopian straight White suburbia Trumpland covets. Everyone else back into the shadows. The only Black people many of them they see are things like the BLM protests, and it scares them to death, although ironically Jan 6, far worse, does not. It’s a wonder Black people don’t assume every White person they encounter is a school shooter or serial killer, because they’re always White. Perhaps they do. They’re human. It’s a human condition, but we’re (allegedly) smarter than that, when we’re using our brains to overcome emotion.

On a Sunday, when we were out walking, we saw people streaming into a Black neighborhood Baptist church. “Let’s go,” I said on a whim. We entered and found a place toward the front, as most of the pews were full. We were directly in front of the full band, with electric guitars and a big worn-out drum set. The musicians counted in and began playing fast and beautiful religious songs as sweat rolled down their faces.

The crowd jumped to their feet and danced and hugged one another, arms raised above their heads, growing into a fervor. It was nothing like I’d seen at the Village of Prayer. It wasn’t fake or devotional to one living man. Instead, it was a joyous celebration of life, and of Jesus. The preacher danced to the center of the altar and motioned the band to slow, then began a passionate sermon about loving one another, helping one another. He mentioned John 4:20.

“Whoever claims to love God yet hates a brother or sister is a liar. For whoever does not love their brother and sister, whom they have seen, cannot love God, whom they have not seen.”

There was no begging for money, or Old Testament threats and admonishment. No forced discomfort and servitude by ordering the flock to kneel, stand, sit, kneel again. It was pure and real devotion. It was pure love of God and neighbor. During the praying times of the service, I bowed my head and asked for answers, asked for guidance. The second sermon focused on family, and the proverbs he quoted seemed to answer my questions.—Farawayer

The above passage from Farawayer speaks to something that has always amazed me. These people, who have been lynched, raped, beaten, enslaved, mistreated, hated on through generations and still, still persist in their faith and joy of life. In my times with Damon’s family and other families, I’ve only seen joy, hope, and faith. My skin color represented the bane of their existence, yet they lovingly accepted me. It’s just incredible to behold, and inspirational. And on the flip side, why is it the hateful always seem so unhappy?

Damon passed away recently. I went to see him toward the end. Same Damon, flirting with the nurses, holding court with the little strength he had left. His body was a shell of the man I knew, but his mind was all there. He rhapsodized about blues music, Gil-Scott Heron lyrics, injustice, regaled me with tales of our adventures together—all properly exaggerated per his style. We talked about those days, and these days. “You remember, Billy. Back then I told you, this shit ain’t never gon’ change.” He was right, unfortunately. He wanted coffee from the hospital cafeteria but I secretly went to Starbucks instead, to his great pleasure. I lingered until I couldn’t stay any longer, and we wiped away tears as we said goodbye. We both knew it was the last time, at least in this life. I miss him every single day. He was legendary.

When I fight for Kamala, I’m fighting for Damon, and I’m fighting for his daughter and his family, all good people I came to know due to the fortune of being his friend. I’m fighting for Barry and the LGBTQ+ community. I’m fighting against Trump and every hateful, horrible, ignorant racist MAGA out there. As I move into this 4th quarter my time here on Earth, one of the things I look forward to most in the afterlife is a reunion with my old friend, and to hear his laugh again. We have a lot of catching up to do, and I can’t wait.

On a lighter closing note, this is one of my favorite Saturday Night Live skits from back in the day. Eddie Murphy in White Like Me. Damon and I watched it many times together.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama … little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. ... With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our Nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together; to pray together; to struggle together; to go to jail together; to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.—Martin Luther King Jr., Baptist minister, civil rights leader, 1963

This pioneer journey continues…

Hey, it took me a few hours to write this journal post for you. Can you spend a few seconds and post it on your socials or forward to others? If so, thank you!

Free subscribers get a free copy of my book of short stories, Rambles and Daydreams. Paid subscribers will get all three books in the noir crime trilogy, Vigilante Angels. I no longer do paid-only posts, because it felt gross to leave people behind, especially those who can’t afford it.

If you read my ramblings, I’ll leave it to your conscience. If you get any value from my writing, consider a donation or subscription, which is priced at a few dollars, the minimum allowed. Half of all money goes to The National Alliance to End Homelessness, the other half pays for expenses.

You can also support me by becoming a paid subscriber below, leaving a small one-time tip at the button below, or by buying my novels at wildlakellc.com, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, or other fine book outlets in paperback, eBook, or audio.

When you buy something using the retail links in our stories we may get a teeny tiny commission, but it never affects your price or our judgement in linking to products we use and believe in. It helps pay for the costs in providing this (hopefully) entertaining content.